Ink and imagination

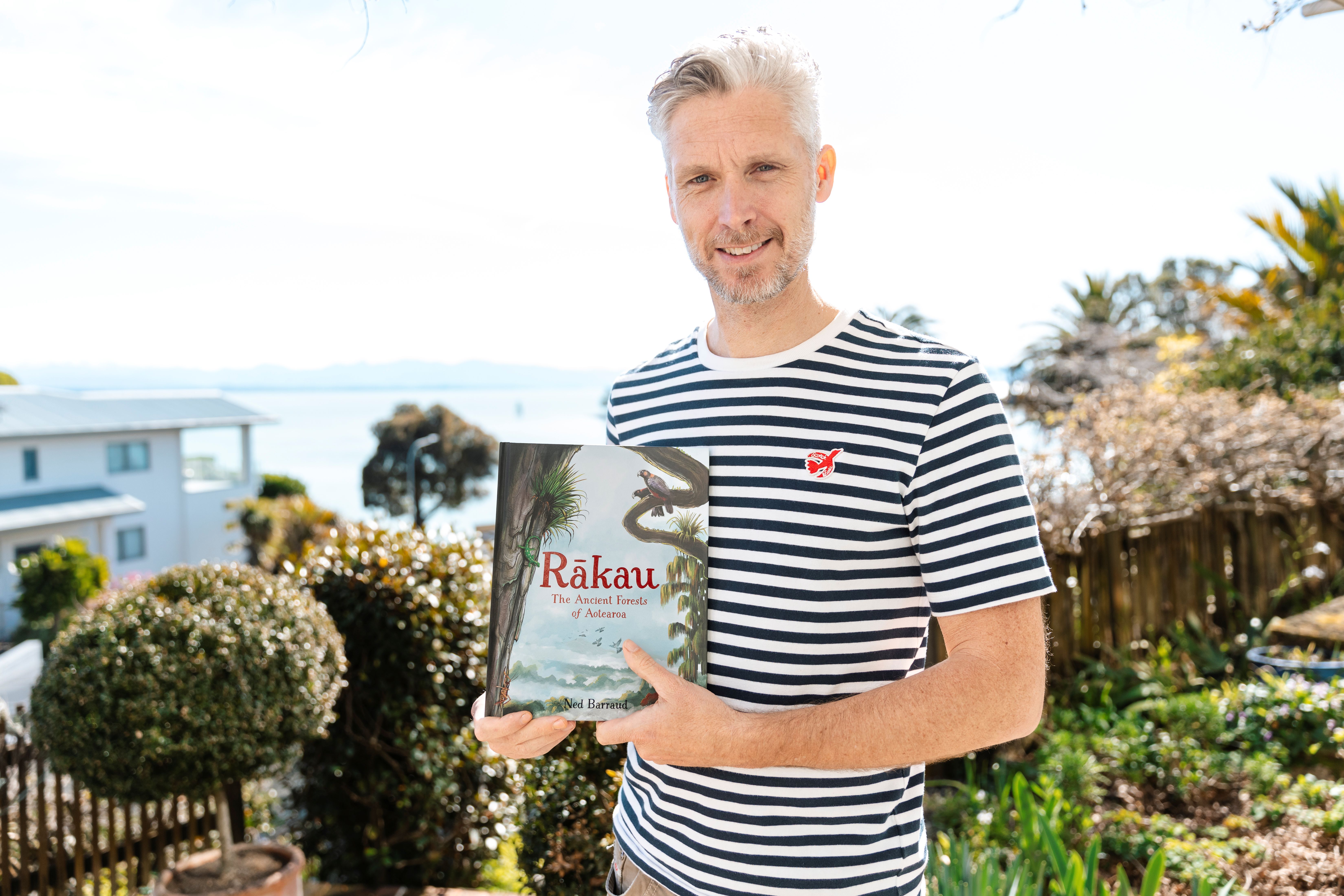

Illustrator Ned Barraud at work in his home studio in Nelson. Photo: Tessa Claus

Once a ‘redundant elf’ on Peter Jackson’s epic film set, Nelson author/illustrator Ned Barraud spent years painting textures for dragons and spaceships. Today he is back in his hometown transforming tuatara, sharks and ruru into children’s books that blend science with wonder. Charles Anderson reports.

After all these years, Ned Barraud still begins with pen on paper. It is the only way, he says, to prise open the door to an idea. A blank screen won’t do. There has to be ink, graphite, a smudge of something physical.

“There’s something about it,” he says from his studio overlooking Tasman Bay. “I can’t do it on a screen. I have to visualise it first, then refine it. Often the drawings end up totally different, I change everything around, but the start has to be on paper.”

He talks with the patience of someone who has made peace with process. There is no rush, no shortcut, no app that can replace the first marks scratched onto a page. Around him, sketchbooks are piled high: some neat, some swollen with years of scribbles and dog-eared corners. He runs his hands over them.

Notebooks like these have been there since boyhood, in this same home, in fact. As a teenager at Nayland College, he would be bent over pages, drawing necromancers and dungeon beasts with the fervour of someone trying to capture a whole other world. He wasn’t the kind of student to shine in class.

“I didn’t excel academically,” he admits. But he was always drawing.

The roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons gave him fuel: the characters, the monsters, the maps. More than that, it gave him the habit of imagining something vivid and then trying to trap it line by line. It is the same habit that has guided his career, beginning with a sketch, then reshaping it, redrawing the path as needed.

Over the years that path has zigzagged across mediums and worlds: from fantasy sketchbooks to ceramics, from Dunedin art school to Weta Digital, from being a Lord of the Rings extra to a decade and a half painting digital textures for Tintin and Avatar. Eventually he walked away from the green-screen world, returning to pen and brush, this time with a focus on children’s books that render tuatara, mangō and ruru with the same loving detail he once gave a dragon’s scales.

The elf chapter came first. His sister-in-law, a casting director, thought he had “elf potential” and slipped him onto the set of The Lord of the Rings. Barraud laughs at the memory, still faintly incredulous.

He spent weeks at Ruapehu during the Helm’s Deep battle shoots, sleeping in the grand old Chateau and filming through the night.

“It was just great fun. You got per diems and half the time you weren’t even on set, so you’d be in the pub with the other elves.”

But when they were on set, it was like a military operation, right down to his colleagues.

“A lot of the extras actually were military. The Uruk-hai, these big guys, they were all ex-army and totally into it.”

The elves were cast in myth but lived like backpackers. There were long nights of waiting, bleary mornings, friendships formed over beers in the snow. Ned remembers the camaraderie more than the battle scenes.

“You felt part of something massive. But at the same time, you knew you were just background.”

Eventually, the call for elves dried up.

“I became a redundant elf,” he says. “There were no more elves needed. That was the end of that dream.”

But one set led to another. A friend helped him into Weta Digital as a rotoscope artist, where he spent long hours cutting actors out frame by frame so backgrounds could be replaced.

“It’s really arduous work,” he says, “but I enjoyed it. I liked the finicky stuff, it’s like creating a little animation.”

He graduated to texture painting, layering the skins of objects both fantastical and everyday. Dragons, castles, alien landscapes, and teaspoons.

“A teaspoon’s harder than a dragon,” Ned says. “It’s so reflective, you’ve got to layer all these maps, displacement, specular, colour, and then render it in light. That’s where it became way more illustrative.”

The films came one after another. Tintin was “so much fun, we had freedom to create the props from scratch.” Avatar, on the other hand, was obsessional in its detail.

“The attention to detail was absurd, they’d nitpick a background speck that nobody would ever notice.”

The work was immersive, sometimes consuming. Fifteen years living and working in Wellington slipped by.

“We’d be in dark rooms for twelve hours a day. It was intense, but I loved the team. My mentor, was just brilliant. He taught me so much about texture, about seeing.”

But the studio changed.

“It became more corporate, more technical. I had a boss who I just didn’t click with. In the end, I didn’t get a new contract. It wasn’t a good conclusion to fifteen years, but probably the right time.”

By then he was already building a second career. His first commissions were for the School Journal, the training ground for so many New Zealand children’s illustrators.

“A friend remembered my drawings from school and pulled me in. A lot of illustrators start there.”

He had story ideas of his own too. One early manuscript, Too Many Fish in the Pool, imagined a boy convinced that every swim meant plunging in with anglerfish and other deep-sea monsters. No publisher picked it up, but it was the beginning of something.

The real break came when Potton & Burton, with a nudge of a family connection, offered him a project with author Gillian Candler. His own manuscript was rejected, but he was asked to illustrate At the Beach.

That book sparked the Explore & Discover series, In the Garden, Under the Ocean, From Moa to Dinosaurs.

“At that time there wasn’t a lot of good non-fiction for kids. That book opened it up, suddenly there was this huge market.”

The series won awards and established Ned as a trusted hand in bringing New Zealand’s natural world to life for children.

Now, he is back where it all began: in his childhood home above Tasman Bay. His parents are older, and he and his wife decided to return to help. Their son Alfie, 14, is at Nelson College for Boys.

From his studio Ned can see across the bay. Often he takes a paddleboard out to Haulashore Island, checking in on the birdlife.

“Living by the water is just incredible,” he says. “I never appreciated it when I was a kid. After years in Karori in Wellington which is pretty landlocked. So, it’s life-changing to be here.”

His days have a rhythm now: mornings in the studio, afternoons punctuated with errands, sometimes a swim, sometimes just staring at the sky over the bay. “It’s slower,” he admits. “But it suits me.”

Inside, the shelves are stacked with sketchbooks, spines bent and pages spilling out. A new exhibition of his work is heading to Whanganui. On the desk are projects in progress: a new book with author Katie Furze, a follow-up to At Home on the Farm, and commissions that range from supermarket murals to a hundred illustrations of birds of prey for an Australian sanctuary.

“It’s busy,” he says. “Busy but not rich. But that’s the life of an illustrator.”

Ned’s work is marked by its mix of precision and imagination. “I’m quite good at imagining something in a different environment,” he says. “I’ll see a real object and picture it underwater, then recreate it. That’s what I’m most known for, imaginative, but highly realistic.”

It is the bridge between fantasy and fact that carries his books. The anatomy of a tuatara, the gleam of a shark’s eye, the shadows in a mangrove swamp, the details are precise enough for science yet infused with wonder. His book Mangōwas recognised at the 2024 Whitley Awards for children’s natural history.

And always, it begins with pen on paper.

“I storyboard on paper, scan it, and then refine it on the computer. But if I don’t start on paper, I can’t get there.”

In an age of screens, he is surprisingly bullish about children’s publishing.

“The industry as a whole is suffering,” he admits, “but kids’ books are undefeatable. You can’t replace them with an iPad. Parents don’t want to give their kids a screen at bedtime. A book is tactile, interactive. You can point, turn pages together. It’s irreplaceable.”

His own children grew up with his books.

“When they were little, they loved them. Now they’re teenagers,” he says, laughing. “That’s how it works, you go from almighty to dirt on their shoe. But that’s healthy. They have to move on.”

Looking back, Ned sees a career sketched and re-sketched, much like his illustrations.

“At Weta, I probably became dead wood,” he says. “Repeating myself. It was time to move on.”

Now, between commissions and books, family and the sea, he feels settled in Nelson. The arc from dungeon sketches to digital dragons to tuatara portraits is not one he could have predicted. But the through-line is clear: pen to paper, imagination to refinement.

“Often the drawings end up totally different,” he says. “That’s how it works. You start somewhere, and you let it change.”

From elf armour to seabird feathers, Ned Barraud has been redrawing his world ever since.